Lindsey Bernstein interviewed Daniel Dennett on Point of Inquiry and at one point she asked him if there was a limit to what humans could understand.

An intuitive answer could go either way. To a person who has just started knowing things, it seems obvious that it just takes time to learn everything ever.

Then you look at our nearest evolutionary neighbor, the chimpanzee. This poor guy can’t even pass a driving test. He is forever cut off from the simplest intellectual feats, like wondering if the mechanism for turning off the refrigerator light is broken. (If the light stayed on, how would you even know?)

So maybe people have similar innate limits.

But at this point, you’re giving yourself too much credit. Because a big part of what makes you so smart isn’t innate at all; it was given to you by others. You don’t even realize the advantages you’ve had. We could call it Sapiens Privilege. You don’t realize, if it weren’t for speech, you wouldn’t be able to pass the driver’s test either.

Behold the sacred milestone on the path to enlightenment. © Mike Mozard

Behold the sacred milestone on the path to enlightenment. © Mike Mozard

It is speech that makes us this smart. The ability to convey our ideas to each other. We can make up words like tiger and names like Tony. Ultimately, that lead us to invent Kellogg’s® Frosted Flakes.

Sure, you have one innate advantage; your brain is bigger than the other apes’ brains. That makes a difference, but words are the real key to it all. If the other apes could understand words, they could do what we do, even if their limited brains meant it would take them longer.

A word is a shortcut. It holds a bunch of thoughts that a million people had to have manually before the word was invented, so you can jump straight from the beginning of the thought to the end without trudging through the middle.

Take your smartphone, for example. There’s this Thing in your phone full of ones and zeros. They’re all in order. Taken as groups they make larger numbers. You can take a number from near the beginning of the Thing and use it to count in order until you reach another section of the Thing. When you reach that place, you can put down numbers you want to save and come back to get them later.

I’m about to lose your interest, even if you’re doing fine at understanding me. So I’ll try it again quicker. Your phone has a flash drive inside. It stories information for you as files. Your phone tells the flash drive what file name to access and you can either save information there or read it.

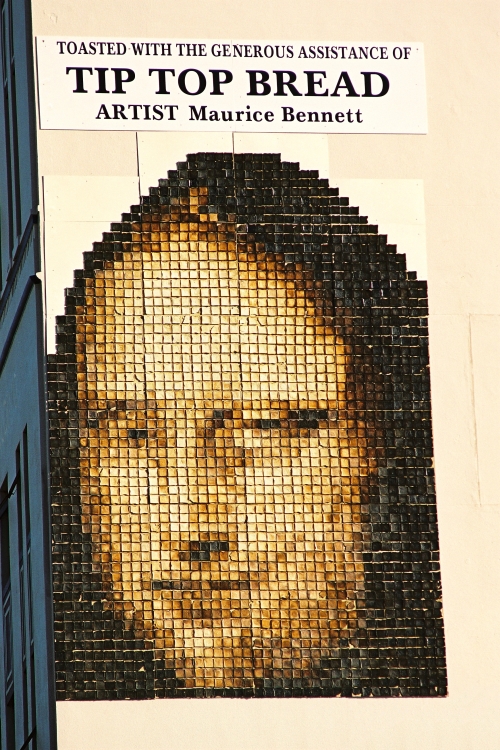

If we didn't have the word fire, we never would have made it here, to Mona Lisa Toast.

If we didn't have the word fire, we never would have made it here, to Mona Lisa Toast.

These words, flash drive, file, file name, information, are all shortcuts for talking about the Thing and numbers stored on it. Without these words, we would spend all day talking about what we want the phone to do, and we’d still only have a tentative grasp on what we were accomplishing.

It’s better to make up the word file and put all that meaning about counting and order and bits into it. This is the trick we used way back when we invented the words fire and warm and third-degree burn.

Now that we have words, we use this trick again and again. We pack the idea of fire inside of “combustion engine”, then we put that inside of “car”, then put that inside of “morning commute”.

And there’s no way to tell whether there’s a limit on this word trick. Maybe we can keep packing words into words to make better shortcuts forever.

Sure some words don’t actually match reality all that well. Words like ghost don’t help us, because they don’t pack ideas about any actual thing that exists. That’s a bad shortcut that gets us nowhere.

But over time, we can discard the words that don’t work and use better words instead. As long as we can stop and try again, there’s no known limit on what words can shortcut for us.

With those shortcuts, the sky is the limit on what we can understand. We just need to understand it a few words at a time.

There might be no limit on what humans can understand. We just have to make shortcuts. https://t.co/2hw5o3xJXn pic.twitter.com/7qjsUFUjeh

— Dan Kuck-Alvarez (@dankuck) January 30, 2017

,

,